At The Library: Libraries put 'Little House' series in new light

November 22, 2019

Keiko Satomi still has copies of "Little House on the Prairie" books translated into Japanese. Libraries are taking another look at the series and its treatment of indigeneous people. More libraries are stocking books casting a wider multicultural net, including the "Birchbark" series by Louise Erdrich.

I grew up reading Laura Ingalls Wilder's "Little House on the Prairie" series in Japan. For me, a young girl growing up in a small country surrounded by oceans, the series was a window into a pioneer family's life on a vast continent I had never seen before. I was particularly fond of all the sensory details (from blowing up the hog's bladder like a little balloon to making molasses candies on the snow) as well as the feistiness of Laura's character, a quality we shared.

The "Little House" series was first published in 1935 and has never gone out of print. It is available in hardcover, paperback, audiobook, video, e-book, as well as large print. The series has been translated into at least 40 languages and continues to be read by children and adults around the world today.

It was about a year and a half ago when the Association for Library Service to Children announced that they voted to change the name of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award to the Children's Literature Legacy Award. The award honors an author or

illustrator whose books, published in the United States, have made a significant and lasting contribution to children's literature. The prize was first awarded to Wilder herself in 1954, and has been won by America's beloved children's authors including Beverly Cleary, Theodor S. Geisel (also known as Dr. Seuss), and E.B. White. According to the ALSC's statement, the decision was made in order to distance the honor from "Wilder's culturally insensitive and dated attitudes towards indigenous people and people of color that contradict modern acceptance, celebration, and understanding of diverse communities."

The first edition of "Little House on the Prairie" contained the line, "There the wild animals wandered and fed as though they were in a pasture that stretched much farther than a man could see, and there were no people. Only the Indians lived there." It was in 1952 that a concerned parent wrote to the publisher to point out the problematic line. It took nearly 20 years for a person to raise the issue. The line got edited with Wilder's permission to "there were no settlers" in later editions.

In 1998, an 8-year-old girl on the Upper Sioux reservation in southwest Minnesota came home with tears after hearing her third-grade teacher read aloud the novel including a character's infamous statement, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian" which is repeated three times in "Little House on the Prairie." The girl's mother, a member of the Wahpetunwan Dakota and a scholar of history and American Indian Studies, devoted months in attempting to have the books dropped from the curriculum. It resulted in the American Civil Liberties Union threatening the school board with a lawsuit over censorship. Wilder's characterization of indigenous people as primitive savages appears throughout the book.

Debbie Reese, a member of Nambe Pueblo in New Mexico and founder of the blog "American Indians in Children's Literature" points out that "people commonly defend savage depictions of Indians with 'that's what the people of that time thought about them' ... Sometimes we say they're just fiction and, in fiction, anything goes. Sometimes, we say that young children should not be presented with the harsh reality of this country's early days, but what 'young children' are we talking about? The lives of many families from minority populations are the ones that experience prejudice and discrimination on a daily basis."

According to the Cooperative Children's Book Center, the percentage of books depicting American Indians/First Nations characters is 1 percent of all the children's books published in 2018. When the books that represent your background are so limited historically, how the characters are represented has a greater impact on your sense of self, and perhaps even on your sense of security. And how would it influence the majority of children?

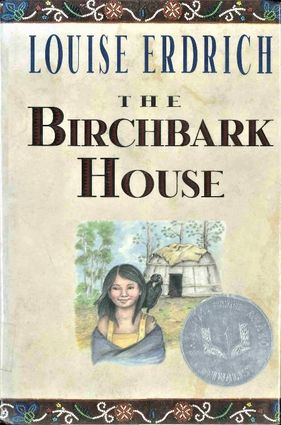

Libraries nationwide are discussing what to do with this series. At some libraries, they have decided to take the series off the shelves. Others opted to keep them in the collection, including the Cloquet Public Library. I personally do not recommend them when asked for book suggestions without pointing out the problematic content or suggesting to utilize it to open a conversation with children and to read it with a critical eye. I also recommend pairing the series with the Birchbark series written by Louise Erdrich, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwa. This critically acclaimed series takes place in about the same time period as the Little House series, yet is written from the perspective of an Ojibwe girl, Omakayas.

There are some empowering movements right in this region. The other day, a member of the Fond du Lac community visited the library to look for children's books about Native Americans. She wanted to learn what kind of books were already out there as she was planning to write a book herself because of the lack of indigenous representation in children's literature. Local author Thomas Peacock and a former faculty member in the education department at the University of Minnesota Duluth, Elizabeth Albert-Peacock, have recently founded a Native-owned non-profit publishing company, Black Bears and Blueberries Publishing. An indie publisher like this plays a significant role in bringing the historically underrepresented people's voices out in the market.

Talking about race with young children or in general is intimidating to many of us. If you decide to open the conversation with your family through books, we have a great resource called "Talking with Young Children (0-5) about Race" compiled by ALSC. Our library and the libraries in the Arrowhead Library System have a rich collection of books on social justice subjects. Many librarians have been intentionally selecting books that represent diverse populations as authentically as possible. This is lifelong learning for all of us and becoming more aware of as many perspectives and voices as possible is a way to step forward. I believe sharing stories and books both from your own perspective and that of others can be a powerful tool for that purpose.

Writer Keiko Satomi is the children's librarian at Cloquet Public Library and the mother of two sons of Japanese, Ojibwe, and Scandinavian heritage.