At 125, Sappi flexes resilience

May 19, 2023

Tom Urbanski

Steve Buscher, superintendent of finishing and shipping, stops to explain how the mill operates with two papermaking machines, the oldest installed in the 1930s. The mill regularly accumulates 1 million hours between lost-time injuries and has survived despite hardships that closed other paper mills. "Sappi's culture is to invest a lot here," Buscher said.

The 125th anniversary of the Sappi mill in Cloquet will bring a company picnic in August, and another surprise following a quarter-century drought.

"For the first time in 25 years we're actually going to have public mill tours in July and August," said managing director Tom Radovich earlier this week. "We've got about 12 dates picked."

Look for details to come on those celebratory events.

Radovich met with local members of the news media prior to a tour of the mill on Monday. He told the story of a paper mill that started in 1898, surviving through three ownership iterations and decades of history - some of it, like the 1918 fire or the 2005 launch of Facebook - seemingly aimed at destroying the local papermaking industry.

"It's really critical we continue the story here at the Cloquet site in terms of the economic impact it has on the region," Radovich said.

For every dollar the company spends on harvesting the mostly aspen and maple trees used in its array of products, Sappi says subsequent activity is equivalent to $4.6 billion annually on the local economy. About half of Minnesota's timber harvest comes via truck to the Cloquet mill.

"It's really a lot of business for a large area, all the way into Wisconsin and Michigan," said Steve Buscher, superintendent of finishing and shipping, of the paper mill's impact on the region.

Jay Arntson is one of more than 2,100 employees in the mill's history to achieve 25 years working with the Cloquet mill. Arntson came in as a temporary vacation replacement and was hired full-time in 1994 for the cleanup crew in the pulp mill. Now, he's president of the United Steelworkers local representing the equipment operators who make up more than half of the mill's 700 employees.

"It's been a great place to work," Arntson said, endorsing the management representation of Sappi as a well-paying, resilient, forward-thinking employer.

"We're part of the apparel industry now," Radovich said, of dissolved pulp from the mill used in the creation of textiles like rayon.

It's a statement that would have been shocking in the 1960s.

Then, a peak of roughly 1,300 people worked at the mill during its transition of ownership from Northwest Paper Company to Potlatch, when it specialized in glossy, coated paper used in making catalogs and represented commercially by a Canadian Mountie.

Now, the mill sells a brand of paper, McCoy, that remains premium in the market and is even used to create gift cards.

"We take our McCoy cover weight and laminate it together to make a sustainable gift card," Radovich said.

The mill entered into the apparel markets in 2013, spending $175 million to be able to make dissolved pulp used internationally in the creation of rayon.

The pulp fibers that are pressed, rolled and dried in hot, steamy production halls are fractions of an inch long individually. They're later dissolved and transformed at textile mills into silky fibers that can stretch up to 2 miles.

Production of the Verve line of dissolved pulp is now roughly equal to the 350,000 tons of paper products the mill produces annually. An additional $25 million investment in the dissolved pulp process in 2019 increased production by 8 percent. Only Target and Best Buy among Minnesota companies export more commercial tonnage overseas than the Cloquet Sappi mill, which sends dissolved pulp to textile plants in Austria, India and Indonesia.

"That market is growing; its annual compounding return is about 5 percent," Radovich said. "It's tied to population - the population increases, the dissolving pulp market continues to increase."

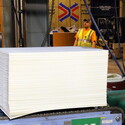

During a tour of the mill, pulp drier superintendent Keith Halvorson led a path through the dissolved-pulp-making process. What starts out as 98-percent wet material becomes a white sheet 190 inches wide and thousands of feet long, serpentining through rollers and dryers until it's scored and cut into manageable bales bound overseas.

"We're at the upper end of technology," Halvorson said. "We are very efficient ... It's a very pure cellulose, and that's just what our customers need."

Additional products leaving the Cloquet mill include LusterCote, a laminate that can be printed on and is used in point-of-purchase displays at places such as Walmart.

"We had no market share in 2015," Radovich said. "Now, we have about 65 percent of the market. We're utilizing our ingenuity to get into some different markets besides coated graphic papers."

The innovations Sappi is employing to remain relevant were necessitated after the advent of Facebook in 2005 and the iPhone in 2007 drove advertisers from print to the internet. Radovich joked that there will always be a market for printed paper products, even if it's a flyer used to send a person to a company's website.

"We've become more of a diversified wood fiber products company, really," he said. "We're helping you do things with a tree, that's our namesake. That's our evolution."

With domestic offices in Boston, Sappi has managed the research and development of new products from a technology center in Westbrook, Maine.

"It starts with sales and marketing saying, 'Hey, I think there's an opportunity here,'" Radovich said.

New products take two to three years to reach the market. Some, like Sappi's dalliance with restaurant menus, never start. In the late 2000s, the company investigated entering the menu market, which was growing and seeing menus changed more frequently. In the end, it wasn't a big enough opportunity to make the leap, Radovich said.

Other markets are more fleeting. If you ordered a picture book from Shutterfly or Snapfish in the late 2000s, it was probably printed on Sappi paper, sources said.

As Radovich and the other officials talked, they spoke about forest management and the pride they took in leaving behind livable habitats. They shared how the plant is, chemically speaking, a closed loop, meaning all of its processes are recycled onsite, and how the mill is 80-percent fueled by renewable energy. One of three turbines onsite is owned by Minnesota Power, but managed by the mill and used to light 5,000 homes.

"We're going to continue to drive toward 100-percent renewable energy," Radovich said.

Asked about what the next 125 years had in store, Radovich noted the likelihood of continually new products.

"Things you don't really think that are a part of your everyday life will become a big part of what we do here," he said, similar to products such as the release liners and LusterCote line.

During his address on Monday, Radovich reflected on a story: during the 1918 fire that devastated the city, the mill was spared after workers and neighborhood residents sprang into action to protect it.

"When you think about the longevity at a facility like this, it boils down to having generations of people that are really interested in forest products," he said. "They've got to make it work."

When it acquired the mill from Potlatch in 2002, Sappi drew down the labor force from roughly 1,100 to 700 - the level at which the workforce has stayed since.

Even artificial intelligence and the next generation of technologies won't impact the need for mill workers, officials said. Every generation has raised expectations at the mill, where every process is staged and every stage well-understood by those who run it.

"You're never going to replace the people," Buscher said. "You're going to need someone who knows how to fix (machines), how to operate them, and who can tell when something goes wrong."

"Innovation won't come from AI," Radovich added. "That takes people, and that won't change."