On The Mark: Child labor offers lessons for life

December 4, 2020

David Parker

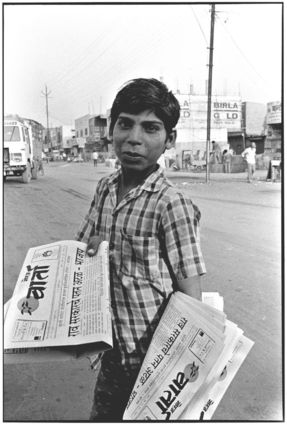

University of Minnesota professor Deborah Levison has spent more than 20 years studying child labor. She's teamed up with photographer David Parker, who captured this newspaper seller in India. For more of their work, visit "Seeing Child Labor" at gallery.lib.umn.edu/exhibits/show/seeingchildlabor.

A good economist colleague and friend of mine, University of Minnesota professor Deborah Levison, has spent more than 20 years studying child labor around the world. Despite many laws formally forbidding child labor, Levison's research finds that children are working all around the world, including in our own region.

She's teamed up with photographer David Parker who has, over many years, captured hundreds of them on film. Levison and historian MJ Maynes have curated a virtual exhibit of the photos, which you can visit online.

I remember visiting Egypt in the 1990s with my 16-year-old son David. In a rickety railroad car travelling south along the Nile, we watched families walking out into the cane fields with their children. My son asked me: "Why aren't they in school?" It was a perfect opportunity to speak about rural poverty and the nature of agricultural work.

Levison has developed a nuanced view of child labor. She argues while it is a necessity for many low-income families, it can also be a great training ground, preparing kids for work life and helping them understand how economies function. Work for pay or income is - for young people everywhere - combined with schooling. Of course, it can be exploitative as well. For that reason, the U.S. and many other countries have historically prohibited child labor.

We've all experienced and observed child labor in our own society. In farm families like those of my husband and friend June Collman, boys and girls alike milked cows, pastured them, raised chickens, collected and cleaned eggs, and helped with the plowing and haying. In cities, some of us delivered daily papers. I had a secret garden in a swamp near our Minneapolis home where, coached by my father, I raised beans and other veggies, selling them to neighbors for a pittance per bag. I was proud of my beans.

In high school, my parents encouraged us to work for spending money. I landed a job at Perkins, then strictly a pancake house, in my neighborhood. I worked evenings and most of the day on Sunday, starting early in the morning.

I had the lowliest job: setting silverware, napkins and filled water glasses on the tables. On Sunday mornings, our busiest, I had to refill the syrup pitchers we placed on each table. I hefted big tin cans full of maple, apricot and blueberry syrup to refill each type of pitcher before they all went through the dishwasher. By early afternoon, when the church crowds had happily departed, I would walk home, my hair and fingernails thoroughly sticky.

On weekends, I also babysat for pay.

Working as children - even if it's unpaid chores like dishes, lawn mowing and shoveling - creates respect for the challenges and quality of work, and pride in good results. By the time we were teens, our parents paid us something for these - I don't remember how much. Deborah offers a wonderful quote from an American farm kid: "Dear Sir or Madam: I am 11 years old. I am writing to ask you to not pass the proposed rule changes for children working on farms. Because we can learn stuff and it seems like you need to learn before you are a teenager or you don't want to learn. It is fun to work on the farm. I like working with animals and it keeps me out of trouble and you get to explore."

My son, David, was eager to work at age 16. He first worked for our modestly-sized public library, where his afterschool job was shelving books. He came home after the first week and complained, sticking his lower lip out. "I'm working under five layers of women, and they don't get along with each other." I replied: "Well, welcome to the sociology of the workplace."

He went on to work at temp jobs like restocking shelves at some version of Office Max and, in a high school semester off in Washington D.C., shelving videos for a television station.

All of these were minimum wage jobs. During college, he worked for a summer on a fiber optics assembly line in suburban Minneapolis, where all of his co-workers were men of color. The next Christmas, he ignored a "no" to a request for time off, came home for the celebration and returned to find he had no job.

Levison's research and Parker's photos provide remarkable windows into children's work around the world, rural and urban. A picture is, truly, worth a thousand words. I encourage you to view the virtual exhibit. Share it with your kids, your friends. Talk with others about their work experiences, help younger people understand the upsides and downsides of the many occupations possible. And that they can change jobs, whether in the same occupation or leaving one that dissatisfies for another. Above all, these photos help place us alongside, for the viewing moments, the millions of children worldwide who are working at young ages. From them, we learn about their economies, the ubiquity of poverty worldwide, and the awesome spirit of young people working under challenging circumstances.

Ann Markusen is an economist and professor emerita at University of Minnesota. She is a Pine Knot board member.